More people of color die as a result of health disparities than at the hands of police. While the murders of countless Americans of color at the hands of police is reprehensible, the medical community is responsible for hundreds of thousands more lives lost. Implicit bias and structural racism within medicine kills and injures as effectively as bullets, but it is often insidious and not as easily captured on a cell phone video. While we must demand change from the police, we must not fail to look within ourselves and our institutions.

Association of Exposure to Police Violence With Prevalence of Mental Health Symptoms Among Urban Residents in the United States

This cross-sectional, general population survey study of 1221 eligible adults was conducted in Baltimore, Maryland, and New York City, New York, from October through December 2017. Police violence was commonly reported, especially among racial/ethnic and sexual minorities. Associations between violence and mental health outcomes did not appear to be explained by confounding factors and appeared to be especially pronounced for assaultive forms of violence.

Connecting Police Violence With Reproductive Health

Since the police-involved deaths of Michael Brown and Freddie Gray, activists have argued for connecting police violence with reproductive justice. We argue that systematic violence, including police violence, should be evaluated in relation to reproductive health outcomes of individual patients and communities. Beyond emphasizing the relationship between violence and health outcomes, both qualitative and epidemiologic data can be used by activists and caregivers to effectively care for individuals from socially marginalized communities.

Risk of Police-Involved Death by Race/Ethnicity and Place, United States, 2012-2018.

American Journal of Public Health

Police homicide risk is higher than suggested by official data. Police kill, on average, 2.8 men per day. Police were responsible for about 8% of all homicides with adult male victims between 2012 and 2018. Black men's mortality risk is between 1.9 and 2.4 deaths per 100 000 per year, Latino risk is between 0.8 and 1.2, and White risk is between 0.6 and 0.7. These disparities were found to vary markedly across place.

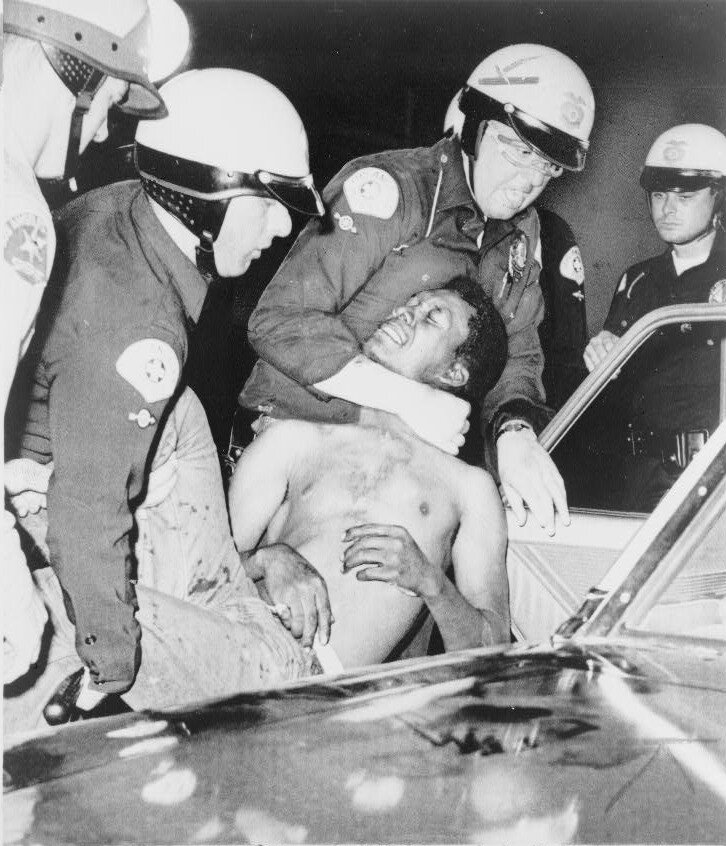

Police violence and the built harm of structural racism

Police killing black Americans is one of the oldest forms of structural racism in the USA. The act traces its roots to slavery.1 Yet it remains a tool for social control that violates black bodily autonomy, engenders racial inequality in access to public services, and re-inscribes the predominant racial order any time police indiscriminately and extrajudicially take a black life

Police Violence, Use of Force Policies, and Public Health

American Journal of Law & Medicine

This Article examines use of force policies that often precipitate and absolve police violence as not only a legal or moral issue, but distinctively as a public health issue with widespread health impacts for individuals and communities.9 This public health framing can disrupt the sterile legal and policy discourse of police violence in relation to communities of color (where conversations often focus on limited queries such as reasonableness) by drawing attention to the health impacts of state-sanctioned police violence. This approach allows us to shift the focus from the individual actions of police and citizens to a more holistic assessment of how certain policy preferences put police in the position to not treat certain civilians’ lives as carefully as they should.

Police Brutality and Black Health: Setting the Agenda for Public Health Scholars

American Journal of Public Health

We investigated links between police brutality and poor health outcomes among Blacks and identified five intersecting pathways: (1) fatal injuries that increase population-specific mortality rates; (2) adverse physiological responses that increase morbidity; (3) racist public reactions that cause stress; (4) arrests, incarcerations, and legal, medical, and funeral bills that cause financial strain; and (5) integrated oppressive structures that cause systematic disempowerment. Public health scholars should champion efforts to implement surveillance of police brutality and press funders to support research to understand the experiences of people faced with police brutality. We must ask whether our own research, teaching, and service are intentionally antiracist and challenge the institutions we work in to ask the same. To reduce racial health inequities, public health scholars must rigorously explore the relationship between police brutality and health, and advocate policies that address racist oppression.

White Coats for Black Lives: Medical Students Responding to Racism and Police Brutality

While protests in response to the deaths of Michael Brown and Eric Garner sparked national dialogue about racism and violence against communities of color, our medical school campuses remained silent and detached. As medical trainees invested in the lives and well-being of people of color, these students talk about feeling called to action by the #BlackLivesMatter movement. Medicine is not immune to the racism that pervades our education, housing, employment, and criminal justice systems. Moreover, racism and police brutality damage the health and lives of people of color, particularly Black people, and must be addressed as a public health crisis.

Police Killings and Their Spillover Effects on the Mental Health of Black Americans: A Population-Based, Quasi-Experimental Study

Police killings of unarmed black Americans have adverse effects on mental health among black American adults in the general population. Programs should be implemented to decrease the frequency of police killings and to mitigate adverse mental health effects within communities when such killings do occur.

Resources

Alang S, McAlpine D, McCreedy E, Hardeman R. Police Brutality and Black Health: Setting the Agenda for Public Health Scholars. Am J Public Health. 2017; 107 (5): 662‐665.

Cooper HL, Fullilove M. Editorial: Excessive Police Violence as a Public Health Issue. J Urban Health. 2016;93 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):1‐7.

Crenshaw KW, Ritchie AJ. Say her name: resisting police brutality against black women. Available at: http://static1.squarespace.com/static/53f20d90e4b0b80451158d8c/t/560c068ee4b0af26f72741df/1443628686535/AAPF_SMN_Brief_Full_singles-min.pdf. Retrieved June 3, 2020.

Hall AV, Hall EV, Perry JL. Black and blue: Exploring racial bias and law enforcement in the killings of unarmed black male civilians. Am Psychol. 2016;71(3):175‐186.

McFarland MJ, Taylor J, McFarland CAS. Weighed down by discriminatory policing: Perceived unfair treatment and black-white disparities in waist circumference. SSM Popul Health. 2018;5:210‐217. Published 2018 Jul 21.

McLeod MN, Heller D, Manze MG, Echeverria SE. Police Interactions and the Mental Health of Black Americans: a Systematic Review. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2020;7(1):10‐27.

Mesic A, Franklin L, Cansever A, et al. The Relationship Between Structural Racism and Black-White Disparities in Fatal Police Shootings at the State Level. J Natl Med Assoc. 2018;110(2):106‐116.

Oh H, DeVylder J, Hunt G. Effect of Police Training and Accountability on the Mental Health of African American Adults. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(10):1588‐1590.